Feynman’s Advice Applied to AI

Understanding Beats Pattern Matching in AI Investing

By Dr. Phillip Alvelda, Managing Partner, Brainworks Ventures

Watch the video: Feynman’s Advice on AI (60 seconds)

Richard Feynman once told me an important secret to understanding anything.

I had the extraordinary fortune to study under some of the most remarkable minds of the twentieth century. Feynman at Caltech, who taught me to think from first principles. Minsky at MIT, who showed me how to ponder how intelligence might be constructed. Sagan at Cornell, who demonstrated how to communicate complex ideas to broad audiences.

Each left a mark on how I approach problems. But Feynman’s insight has become a powerful compass for AI investing.

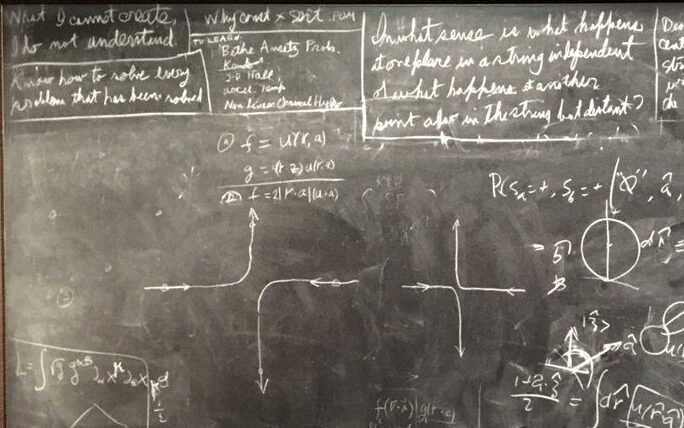

“What I cannot create, I do not understand.”

That single sentence, scrawled on his blackboard and discovered after his death, it was a mantra so important to him that he repeated it in many forms, in class, in seminars, and even in casual meetings. It captures something essential about the difference between genuine knowledge and superficial familiarity. And in the current AI investment landscape, that difference has never mattered more.

The Gap Between Knowing and Understanding

Feynman was famous for his ability to explain complex physics in simple terms. But his real genius was recognizing that explanation and understanding are different things.

You can know the name of something without understanding it. You can describe how something behaves without grasping why. You can memorize formulas and definitions and still be completely lost when facing a novel problem.

True understanding, Feynman insisted, means you can build it yourself. Not necessarily in practice—he wasn’t suggesting every physicist needed to construct a particle accelerator. But in principle, you should be able to derive the result from first principles, explain each step, and predict what would happen if conditions changed.

If you can’t do that, you’re pattern matching, not understanding. And pattern matching breaks down precisely when you need understanding most—in novel situations where the patterns don’t apply.

The AI Investment Problem

AI has become the hottest investment category in venture capital. Hundreds of billions of dollars are chasing anything with artificial intelligence in the pitch deck. Fund managers who couldn’t explain the difference between a transformer and a diffusion model are confidently backing AI startups.

Most of them are pattern matching.

They see a company that looks like a previous successful company. They see a team that resembles a previous successful team. They see metrics that match the metrics of previous winners. They invest based on surface similarities without understanding what’s actually happening beneath the surface.

This approach works when conditions are stable and the future resembles the past. But AI is a domain of rapid change, where yesterday’s patterns may not predict the tomorrow’s outcomes. The investors who are pattern matching will be caught off guard when conditions shift. The investors who actually understand will adapt.

The gap between these two groups is widening. As AI becomes more sophisticated, the technical knowledge required to competently evaluate investments is increasing. The pattern matchers are falling further behind, even as they continue to confidently deploy capital.

What Understanding Looks Like

Let me be specific about what I mean by understanding in AI investing.

When I evaluate an AI company, I’m not just asking whether the technology works. I’m asking how and why it works. What are the underlying mechanisms? What assumptions does it depend on? Under what conditions would it fail? How does it compare to alternative approaches, and what are the tradeoffs?

I’m asking whether I could build it myself. Not whether I would—I’m an investor now, not a builder. But whether I understand the technology deeply enough that I could explain each component, derive the key insights, and predict how it would behave in novel situations.

This level of understanding lets me distinguish genuine innovation from clever repackaging. Many AI startups today are thin wrappers around existing APIs—they’ve built a user interface and some prompt engineering on top of foundation models created by others. That’s a legitimate business, but it’s a very different investment than a company that’s created novel technology with defensible intellectual property.

Understanding also lets me evaluate technical risk accurately. When a founder claims their approach will achieve certain performance characteristics, I can assess whether that claim is plausible based on the underlying mechanisms. I can identify the assumptions that might not hold, the failure modes that might emerge, the competitive responses that might erode advantages.

Pattern matching can’t do any of this. It can identify surface similarities to past successes, but it can’t evaluate the substance beneath the surface.

The Education That Made This Possible

I didn’t develop this understanding in business school or at a venture capital firm. I developed it over thirty-seven years of working in AI, starting in research labs and continuing through founding companies and directing government programs.

At Caltech, Richard Feynman taught me to always go back to first principles. Don’t accept received wisdom. Don’t trust elegant explanations that you can’t derive yourself.

At MIT’s AI Lab, Thomas F. Knight taught me to take things apart and fiddle with them until you understand how each piece works, what it does, and why it’s necessary.

Marvin Minsky showed me how to think about intelligence itself. What are the computational requirements for perception, reasoning, learning? What are the different approaches to building systems that exhibit intelligent behavior, and what are their strengths and limitations?

At Cornell, Carl Sagan demonstrated how deep understanding enables clear communication. If you really understand something, you can explain it simply. If you can’t explain it simply, you probably don’t understand it as well as you think.

These mentors gave me something that can’t be acquired quickly: the foundation for genuine understanding of AI and the neuroscience that underpins it, rather than superficial familiarity with it. That foundation has been refined through decades of building AI systems, investing in AI and neuro-tech companies, and watching which approaches succeed and which fail.

Why This Matters Now

The stakes for understanding versus pattern matching have never been higher.

AI is moving faster than any technology transition I’ve ever witnessed. The capabilities available today didn’t exist even two months ago. The capabilities that will exist in two years are difficult to predict even for experts. In this environment, simple pattern matching based on historical data is almost guaranteed to fail.

At the same time, more capital is flowing into AI than ever before. Investors who don’t understand the technology are making bets they can’t evaluate. Many of them will lose money—not because AI isn’t transformative, but because they’re backing the wrong approaches, paying the wrong prices, and missing the opportunities that genuine understanding would reveal.

The gap between investors who understand and investors who pattern match will translate directly into performance differences. The funds that can evaluate AI technology at a deep level will identify opportunities others miss and avoid traps others fall into. The funds that can’t will be at the mercy of luck and hype.

Feynman’s Standard

I apply Feynman’s standard to every AI investment I consider: Do I understand this technology well enough that I could build or have it built myself?

When the answer is no, I don’t invest. Not because I need to be able to build everything—I’m an investor now, not an engineer. But because if I can’t understand the technology at a fundamental level, I can’t evaluate it competently. I can’t distinguish breakthrough from incremental. I can’t assess risk accurately. I can’t provide useful guidance to founders or Limited Partners.

This standard limits what I invest in. There are AI domains where my understanding isn’t deep enough to meet Feynman’s bar. I stay away from those domains, even when the pattern matching suggests they might be good investments.

But within the domains where I do have deep understanding—neural architectures and interfaces, computer vision, natural language processing, the intersection of AI with the technologies I’ve spent decades building—I can evaluate opportunities that pattern matchers miss. I can see through marketing to substance. I can identify the technical choices that will determine success or failure.

That understanding is the edge Brainworks brings to AI investing. Not just familiarity with the space, but genuine comprehension of how these technologies work and why they matter. Feynman’s standard, applied consistently, will separate investors who can navigate this transition from those who will be swept away by it.

What I cannot create, I do not understand. And what I do not understand, I do not invest in.

Want to discuss what deep technical understanding means for AI investing? Reach out at alvelda@brainworks.ai or visit brainworks..